私が「データ時代」と名付けた特集号の編集作業が慌ただしく進む中頃、上級副編集長のライアン・ブラッドリーは、スティーブン・ウルフラムがデータの歴史的進歩における重要なマイルストーンを年表にまとめていることに気付きました。私たちは、適切に活用されれば世界を明らかにし、影響を与えるデータの急成長する力に関する私たちの分析に、この年表が文脈を結びつける優れた接着剤になると考えました。幸運にもウルフラムは同意し、年表は雑誌のページの下部に結合組織として掲載されました。ウルフラムは当時、ワシントン DC で第 2 回年次 Wolfram Data Summit を開催する予定でした。これは、データベースのキュレーターや提供者、オープンソースの専門家が集まり、幾何級数的に拡大するデータの恵みを最も効果的に育成、処理、解放する方法を議論する場です。ウルフラムのデータ処理アンサー エンジンである Wolfram Alpha は、とてつもなく野心的で楽観的な事業です。彼独自のMathematicaソフトウェアの強力なアルゴリズムと、強力なデータキュレーション技術を組み合わせることで、ユーザーが気づいていないかもしれない疑問に答えようとしています。データについて語り合うのに興味深い人物だと思いました。

電話は約1時間45分続きました。私は、彼のキュレーターとしてのスキルを活用させてくれたことへの感謝と、急成長するビッグデータの力に関する私たちの提案に賛同するかどうかを尋ねました。それから、ウルフラム氏による、宇宙の起源と法則をアルゴリズム的に探求する方法についての説明まで、様々な話をしました。これは、基本的に、自然界の華麗で還元不可能な複雑さ(人間工学の反復的で単調な単純さとは対照的)を象徴するものでした。とても楽しい時間でした。読みやすくするために全文を編集し、読者の便宜を図るため少しだけ簡潔にまとめましたが、それ以外は全文をお読みいただく価値があると思います。楽しい旅を。

マーク・ジャノット:まず、データ特集号でタイムラインの使用を許可していただき、ありがとうございます。読者の皆様に特集全体をスムーズに読み進めていただき、この特集号を美しくまとめる上で、タイムラインは大変役に立っています。本当に素晴らしい記事です。

スティーブン・ウォルフラム:私は文明の進歩において体系的なデータが重要だと常に考えていました。しかし、ポスターを制作する中で、文明の重要な方向性を創造する上で様々なステップが、あれこれに関する体系的なデータ、あるいは人々がデータの入手可能性を確信していたからこそ可能になったのだということを、改めて実感しました。もちろん、歴史の過程では、大量のデータが収集された結果、悪い出来事も起こりましたが、私は前向きな進歩に目を向けたいと思っています。

タイムラインからネガティブな部分を省くことを選択しましたか?

私は歴史をそれほど詳しくは知りませんが、人々の国勢調査ができるようになれば、その人たちを嫌いだと判断でき、国勢調査に基づいてその人たちの居場所を把握することができます。

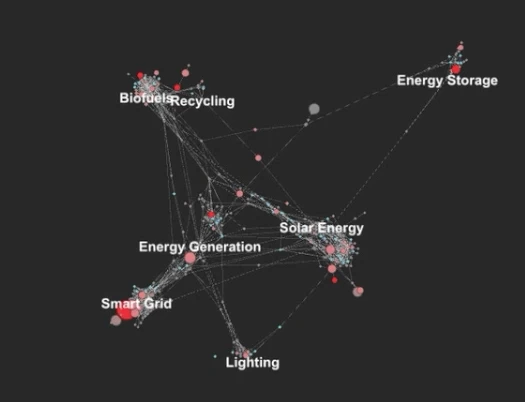

何事にも言えることだと思います。進歩につながるものは何でも、悪用やマイナスの結果を招く可能性があるのです。私たちが公開している記事の一つは、アルバート=ラースロー・バラバシと、彼のハブとノードに関する現在の考え方、そしてどれが行動ハブとノードであるかを学ぶことの意味についてです。それを理解すれば、その知識を使ってシステムを制御できるようになります。もちろん、そのようなことから期待できるプラスの結果はたくさんある一方で、潜在的なマイナスの結果も容易に想像できます。

私はこの分野の二つの側面に関わってきました。一つはコンテンツとしてのデータ、もう一つはデータによって表現される膨大な集合体の科学です。その両方の側面で、様々なことを見てきました。テロ組織がどのように組織されているかを知るためにネットワークを理解することに苦慮する人々や、支持者ではなく重要な人物だけをターゲットにすることでマーケティング予算を最小限に抑える方法を見つけ出すためにネットワークを理解することなど、様々なことを。ちょっと興味があるのですが、データに関する問題では一体何を扱っていらっしゃるのですか?

そこでまず、データ収集、保存、処理能力の指数関数的な成長曲線は、データが世界を理解し、変化させる上でどのように役立つかという点で、真のパラダイムシフトの瞬間をもたらしたという考えについて触れておきたいと思います。あなたはこれに賛成ですか?そして、これはあなた自身のデータと計算に関する研究とどのように関連しているのでしょうか?

ここにはいくつかの異なる分野があります。まず、「データ」と言えば、今日の世界におけるデータの源泉は何でしょうか?データ源の一つは、人々が集計したデータです。例えば、国勢調査データや化学物質の特性データなどです。これらは主に人間が集計したデータです。今日では、様々な分野で非常に大規模なデータリポジトリが存在します。その多くは30年前に開始され、徐々に構築されてきました。これらのデータリポジトリは、当初はメインフレーム、その後の世代のコンピュータの存在によって可能になりました。多くの人々がこれらのデータリポジトリの作成に着手したのは、まさにこのためです。つまり、データの第一の源泉は、人間によるデータの集約です。もう一つのデータ源は、最近になって大規模にオンライン化が進んでおり、センサーデータです。現在、世界中の地震計や交通流センサーなど、何らかの公開センサーデータが存在し、人々がそれぞれの目的で使用している、はるかにプライベートなセンサーベースのデータも数多く存在します。そこから、極めて均質なデータの巨大な奔流が生まれます。それは「この川の水位を時間の関数として、過去何世紀にもわたって毎分記録したもの」です。

各センサー データの各セットではデータが均一ですが、クロス計算を可能にするような方法では、センサー データ セット間で必ずしも均一である必要はありませんか?

その通りです。しかし、個々のデータポイントを収集するために特別な労力はかかりません。そして3つ目のデータソースは、基本的に計算宇宙から生成されるデータ、つまりアルゴリズムを使って解き明かすことができるものです。これらのアルゴリズムを実行して解き明かすには多大な労力がかかるかもしれませんが、一度解き明かせば、それを保存してデータとして使用することができます。数学関数の特性などをまとめた巨大な表などを作成し、それぞれのエントリの作成には多大な労力がかかりますが、一度作成すればすぐに使えるものになります。私はこれらを実用的なレベルでデータのソースだと考えています。さて、問題は、人々がこのデータを使って何をするのかということです。そこで問題になるのは、生データそのもの、つまり専門家は生データそのものを活用できますが、他の人々は通常、生の生データそのものを必要としません。彼らは通常、このデータに基づいて何らかの質問に答えたいと考えており、そのためにはデータだけでなく、知識、そしてその知識に基づいて質問に答える能力が本当に必要なのです。

数年前のTEDで、ティム・バーナーズ=リーは聴衆を率いて「もっと生のデータを!」と叫んでいました。つまり、彼はデータウェブの構築に取り組んでいるということですね。そして、Wolfram Alphaでのあなたのプロジェクトは、生のデータを提供することではなく、生のデータを意味のあるものに変えるインターフェースを提供することです。

そうです。私たちがやろうとしていることは、私にとって、こうしたデータの素晴らしい点は、世界に関する多くの疑問に答え、世界で起こりうる出来事などを予測できることです。しかし、どのようにそれが可能なのでしょうか?専門家が「このデータがあります。何月何日の天気が分かっていて、何月何日の経済状況も分かっています。ですから、そこから何かを推測することができます」と言うことは可能です。しかし、私が興味を持っているのは、コンピューターの前に立って「わかりました。この質問に答えてください」と言えるようになるかどうかです。

ですから、疑問が生じたときに、生データを探し出して分析するという、非常に複雑な手段を講じる必要はありません。分析は自動的に、魔法のように行われます。

そうですね。例えば、地球上の自分の位置から月が今どこに位置しているかを調べようとしているとします。そこには基礎となるデータがあります。月の軌道要素、緯度経度、様々なタイムゾーンデータなどです。しかし、それらの軌道要素を適用して、「これらの座標系を使えば、この計算ができる」などと判断するには、ある程度の距離があります。これが一つの例です。もう一つの例としては、例えば、何かの価値と経済指標、そしてある国の人口が分かれば、一人当たりの値を算出し、それを世界の他の国と比較できる、といったことです。後者の場合は、ほとんど浅い計算で、ほとんど計算のようなものです。前者の場合は、実際に生のデータから計算を行い、答えたい質問に答えるために、ある程度の物理学が必要になります。人々に「人工衛星の軌道要素表がありますよ」と言うのは簡単です。「なるほど、いいですね。もし天体力学の授業を受けたことがあるなら、そこから国際宇宙ステーションが今どこにいるのかを実際に計算できます。これは、データを超えた計算ステップのようなものです。つまり、私にとってデータは、世界について様々なことを知るための基盤となる層です。実際には、データとアルゴリズムという2つの大きな要素が必要です。人工衛星の例では、データは「軌道上の衛星の要素は何か?」というものです。そしてアルゴリズムは、「衛星は重力場の中でどのように伝播し、「次に衛星はいつ地平線から昇ってくるのか?」という私の質問に実際に答えてくれるのか?」というものです。

データの活用方法について私たちが理解しようとしてきた点には、さらに2つの課題があります。1つ目は、データは存在するものの、実際にどのようにアクセスし、データを要求するのかということです。2つ目は、ある都市の規模に関するデータは存在するかもしれないが、一体どの都市のことを言っているのかということです。その都市には俗称や政府による公式名称などがあるかもしれません。では、実際に物事をどう呼べばいいのか?これは生データの一部ではありません。センサーが拾ってくれるものでもありません。これは、データと人間の経験、そして物事の捉え方を結びつける奇妙な要素なのです。

人間とデータの間に仲介役を務める機械知能は、データにアクセスできるようにするために人間の言語を理解する必要があります。

この知識を人間が理解できる形で提供する必要があります。そのためには、人間の情報吸収の仕方をある程度理解する必要があります。人間は人間から学ぶ必要があります。センサーはデータ自体で収集できるものはすべて収集できますが、システムが私たちが求めているものを理解できない限り、それらと結びつけることはできません。そして、このデータに関するもう一つの重要な点は、多くの場合、多くの結果や答えを生成できますが、次に問題となるのは、それらをどのように提示するかということです。これもまた、非常に人間中心的です。「これが結果です。このマイクロスパゲッティの中に百万個のノードが絡み合った巨大なネットワークです」と言うこともできますが、人間はそれを意味のある形で理解することはできません。この知識を人間が理解できる形で提供する必要があります。そのためには、人間の情報吸収の仕方をある程度理解する必要があります。これは生データの上にメタレイヤーとして働くもう 1 つの要素です。つまり、それを人間にどのように提示すべきかということです。 Wolfram Alpha で興味深いと感じたことの 1 つは、人々に答えを 1 行で与えるという実験を行ったことです。人々が「イタリアの GDP はいくらですか?」のような質問をすると、答えがあります。何兆ドルという何兆ドルという数字です。人々は実際には答えだけを知りたがっているのではないことがわかりました。その数字の由来や、世界各国での順位、現地通貨への換算額など、プロットの方にずっと興味があるのです。そして人々は、情報を吸収するために、周囲の状況を必要な何かに素早く同化します。

しかし、アンビエント・コンテキストの限界をどう定義すればいいのでしょうか?その方向にあまりにも広範囲に進み続けると、再びその藪をかき分けて進むことが不可能になってしまうかもしれません。

そうです。例えばWolfram Alphaでは、まず何を提示するか、という点に多くの労力を費やしてきました。そして「もっと見る」ボタンを押すと、さらに情報が表示され、それを何度も何度も繰り返してリンクをたどり、どんどん進んでいきます。つまり、何が最も重要なのか、次に何が重要なのかということです。これらはすべて、基礎となる生データを超えた計算知識の提供に関わるメタ情報なのです。

情報をどのように提示するか、焦点距離はどの程度にするかといった決定は、人間が行う必要があるのでしょうか、それともある程度は自動化できるのでしょうか?

ある程度自動化できました。例えばグラフを作成する場合など、一定の基準があります。人間の経験から抽象化を図り、見栄えが良く分かりやすいグラフを作成するための設計原則とは何かを探求しました。そして、それらの設計原則を自動的に適用できるようになりました。例えば、ネットワークをレイアウトし、これがあれとあれにつながっていることを示す場合、そのレイアウトプロセスをほぼ完全に自動化しました。これは、何年も前に人間にレイアウトを依頼していたことを覚えています。これがあれとあれにつながっていると分かっていると、良いレイアウトを作るのはかなり難しかったのです。実際、かつて自分で大きなレイアウトをたくさんやったことがあります。文字通り紐を用意して、色々なものを配置して、様々な場所に置くのです。見た目が良くて理解できるときもあれば、そうでないときもありました。これは、私たちが完全に成功した例です。私たちはそのプロセスを完全に自動化しています。

そもそも良いグラフを作るにはどうすればいいかを考えるプロセスはどうでしょうか?

そうですね、何がこれを良くし、何が良くないかを示す原理を予言することはできます。必要に応じて、それらの情報を人間の認知理論に結び付けることもできます。私がこれまで行ってきたことは、通常、それよりも実際的なものでした。人間の認知について知っていることから少し情報を得て、これが設計ルールであるとだけ述べ、次に、これらの設計ルールを満たす視覚出力を生成するアルゴリズムを作成する方法を考え出しました。そのレベルでは、235インチなどの数値を入力するときに、次のような質問をすることができます。質問は、235インチに基づいて何を知りたいかです。おそらくそれをフィートに変換したいかもしれませんし、メートルに変換したいかもしれません。たとえば、ミクロンに変換されることは特に気にしないかもしれません。人間がそれを何に変換してほしいかをどうやって判断するかという問題があります。この特定のケースでは、様々な単位についてそれを解明するために、Webや学術論文などを調べ、全体を分析しました。インチ、メートル、センチメートル、ミクロン、ナノメートルといった単位について人々が話すとき、1000万ナノメートルと言うでしょうか?おそらくそうではないでしょう。230ナノメートルと言うでしょうか?もちろんです。Webというデータセットを見ることで、人々が単位などについてどのように話しているかについて、ある分布を推測できることがわかりました。

235インチのような場合、皆さんのような計算エンジンにそれをそのまま入力する人はどれくらいいるでしょうか?「235インチをメートルで」とか、そういう風に言った方が自然だと思います。そこまで踏み込んでいないのは驚きです。

そうではありません。彼らはそうしません。なぜなら、もしあなたが何かについて考えてみると、例えば何かが235インチだと分かるとします。そして「それは一体何だろう?」と自問します。そこで入力すると、フィート、メートル、センチメートル、ヤードといった単位の数値が表示されます。すると彼らは「それが知りたいことだった」と言うのです。

したがって、メートルで表すということは、彼らが知りたいことを理解できないことになります。

例えば、読者がポピュラーサイエンス誌の記事を読んでいて、これこれこういうものの大きさ、リットル数とか何とかが書いてあるとします。読者は「あれは何だろう?」と考え、入力してリンクをクリックすると、実際には22.3ガロンとか何とかだと表示されます。では、コカ・コーラのボトルの実際のサイズを何倍にするかという比較も生成してみましょう。すると読者は「ああ、これでわかった。これで何かできる」と思うでしょう。これは、生のデータを、人間が実際に持っている知識の地図のようなものに関連付けるものです。重要なのは、実際のデータから人間にとって有用なもの、人間が理解できる有用なものへとどのように変換するかです。その一つは、生のデータから実際に計算を行う必要があるということです。もう一つは、その計算結果を人間によく合うように提供する必要があるということです。

データを人間が理解できるようにするために必要な問題の範囲、あるいは数は、事実上無限であるように私には思えます。人々が理解できるようにするために、どのように翻訳する必要があるかを考えるという作業は、途方もなく骨の折れる作業に思えます。

世界には一体どれほど多くの種類のものがあるのか、どれほど多くの異なる知識領域があるのか、考えてみてください。例えば、私のようなデータを扱う人間は、世界には600万本の道路があるとか、一般的な食料品店には3万種類の商品があるといったランダムな事実を話すことができます。こうした事実を山ほど読むことはできますが、こうした領域の数は限られています。それぞれの領域には、その領域内に似たようなものが大量に存在します。そして、その領域の数は数千に及びます。Wolfram Alphaでは、こうした数千の領域を解析してきました。ある領域に出会うたびに、新しく異なる問題が生まれます。例えば、植物という領域を一つ選んでみましょう。植物には様々な問題があります。どんな種類があるのか、どれくらいの高さになるのか、どのように収穫されるのか、といった問題です。植物は特定の臨界温度で成長し、発芽を始めます。これらが気候とどのように関係しているのか、そしてこれら全てがどのように繋がっているのか、考えてみてください。植物のような新しい領域を扱うとき、「これはこれとこれとこれとよく似ているけれど、それぞれ独自の細かい点があり、それを処理しなければならない」と考えます。これらの領域それぞれにかなりの労力がかかりますが、その労力には限りがあり、しかもその数も限られています。Wolfram Alphaプロジェクトでは、このプロジェクトが全く不可能ではないと判断するに至った2つの基本的な観察結果がありました。

それを理解した日は素晴らしい日だったに違いありません。

このプロジェクトを始めた当初は、結論に確信が持てませんでした。その一つは、世界には膨大なデータがあるものの、その量は有限だということです。ただ、膨大な量があるわけではありません。例えば、Web のようなものです。Web は非常に巨大です。しかし、どれほど大きいのでしょうか?Web 上にはおそらく 100 億ページほどの意味のあるページがあるでしょう。Web は巨大ですが、その数は有限です。参考図書にはどれだけの量のデータが収蔵されているでしょうか?最大の参考図書図書館はどれくらいの大きさでしょうか?これらの参考図書図書館にはどのような資料が収蔵されているでしょうか?確かに巨大ですが、それは数兆、あるいは数千兆の要素を持つものであり、具体的な数字を挙げることができるものです。その大きさを定量的に測ることはできますが、確かに巨大ではありますが、無限に大きいわけではありません。このようなことをするには、無限にスケールアップする必要があると言う人がいますが、実際には無限にスケールアップする必要はありません。世界は有限な場所です。広大ですが、有限です。

私たちが話している数字の規模はあまりにも巨大で、まるで無限であるかのように思える人が多いでしょう。それはあまりにも気が遠くなるような気がします。

こういうことに関しては、私は幸運にも、難しそうだからといってできないわけではない、という馬鹿げた自信を培ってきました。例えば、アンペールの法則や万有引力の法則など、世界には名前のついた法則がいくつあるでしょうか?5,000から10,000くらいです。それはどういうことでしょうか?ええと、全部実装するには50万行ものMathematicaコードが必要になるかもしれません。膨大ですが、有限です。

これが最初の洞察です。

ウェブ上にはおそらく100億ページくらいの意味のあるページがあるでしょう。そうですね。2つ目は、機械が質問の答えを計算できるという概念を、私はなんとなく想像していたことです。それはまさに知能活動です。1950年代や60年代のSF映画で、人々がコンピューターに近づいて話しかけ、コンピューターが答えを出すというのを見たことがありましたよね。私はずっと、そのコンピューターの中に必要なのは汎用人工知能だと考えていました。質問にきちんと答える唯一の方法は、人間が考え、答えを見つけるときの行動を模倣することだと。私が取り組んだ多くの基礎科学の結果、私はある結論に至りました。宇宙では、物理学や他の場所で、高度なものがどのように起こっているのか。知能のように見えるものはどのように見えるのか。自然界では、高度なものはどのように起こっているのか。自然界で起こっていることの高度なことは、私たちが心でできることの高度なこととどのように比較できるのか。私が気づいたのは、これは私が計算等価性の原理と呼んでいるものの一部ですが、自然界や計算宇宙で起こること、つまりプログラムや物事の可能性と、私たち人間が知性を持って行えることとの間に、実際には明確な区別がないということです。もし誰かが「人工知能を作るには魔法のようなアイデアが必要で、それは通常の計算には存在しない、特別なアイデアだ」と言ったとします。しかし、私が気づいたのは、知的なものと単なる計算的なものとの間に、そのような明確な境界線は実際には存在しないということです。つまり、専門家である人間が答えてくれると期待されるような質問に答えるために、AIを丸ごと構築する必要はないということです。これほど哲学的な問題が、実際に1500万行のコードを作成し、数十億台のサーバーを稼働させるようなサイトを作るという現実的な結果をもたらすというのは、少し驚きです。知的であることの意味という哲学的な問題が、実際にこれほど実践的な結果をもたらすというのは、ある意味魅力的だと思います。少なくとも私にとっては、計算知識を扱うシステムの構築に成功するために人工知能を発明する必要はない、という点で、確かにそうでした。さらに、この問題に取り組み始めてから、人間は人工知能について全く間違った考え方をしていることに気付きました。なぜなら、そうすると「人間と同じように物事を推論しよう」という思考モードに陥ってしまうからです。例えば、物理学の問題を解決しようとしているとしましょう。物理学の問題について推論します。「この機械が別の機械を押すと、これがこうなる、これがこうなる、と」といった具合に。こうして論理的な推論の連鎖が生まれます。しかし、これはシステムが実際に何をするかを理解する上で、非常に非効率的な方法であることが判明しました。もっと効率的な方法は、150年前に人々がそれらの事柄を表すために発明した方程式を設定し、最新の科学的手法を使って答えを導き出すことです。

では、厳密には AI ではないあなたの AI は、人間が考え出すようなめちゃくちゃで回りくどい方法よりも優れた方法を独自に考え出す必要があるのでしょうか、あるいは、そうする必要があれば AI が考え出すようにプログラムする必要があるのでしょうか?

肝心なのは、「答えを計算できるか?」ということだと思います。では、答えを計算する方法を見つけるとはどういう意味でしょうか?どんなに高度なアルゴリズムであっても、答えを導き出すだけでなく、ある程度の「方法」を見つけ出す作業は行っています。「方法」を見つけることと「答えに到達すること」の間には、実際には区別はありません。少し話題を変えますが、先ほどおっしゃっていたことの一つ、そして私が疑問に思っていることの一つは、私たちは今、世界について多くのことを容易に計算できる世界に生きているということです。多くのことを理解でき、ある程度のことを予測でき、何かについて質問するだけで、答えや予測などを導き出すことができます。これが人々の行動の未来にどのような意味を持つのか、どのように考えるべきでしょうか?テーマの一つは、人々が物事のやり方を推測するだけの時代から、より正確に何をすべきかを実際に計算する時代へと移行しているということです。こうした現象はますます多くの場所で見られるようになり、時には私たちが使うデバイス内部でも起こります。デバイスは自動的に計算を行い、カメラのフォーカスなどを自動的に調整します。GPSはどこへ行けばよいかを判断します。時には、単に私たちに何かを教えてくれることもあります。そう遠くない将来、知識の提供はより先制的になると思います。今のところ、私たちが得る知識の多くは、自ら求めなければなりません。Wolfram Alphaに歩み寄り、質問をするのです。興味のあることを事前に教えてくれるわけではありません。今後は、興味のあることを事前に教えてくれるような仕組みがますます整っていくと思います。これは、今後数年のうちに出現すると思われる、全く別のデータの世界、つまりパーソナルアナリティクスの世界と関連しています。自分自身に関するすべてを記録し、結論を導き出します。私のような人間は、データに興味を持っていたので、この20年間、入力したすべてのキーストロークを記録してきました。他にもたくさんのものを記録してきました。普段はそれほど頻繁には見ないのですが、過去10年ほどの自分のデータをすべて見直し、そこから自分自身について何が学べるかを探るという大きな取り組みをしようとしていました。これは、生のデータを持っているだけでも面白いのですが、そこから計算したり、どのように提示するかがわからなければ、すぐには役に立たないという良い例です。自分自身について記録された情報に基づいて、関連性のある知識を事前に提供し、有用な知識を計算できるようになることがますます増えていくと思います。

結局のところ、こうしたことから得られる最も有用な洞察は、どのような質問をすべきかという洞察です。あなたは、そもそも考えもしなかったような自分自身のことを知りたいと思うでしょう。そして、そこから得られる情報に基づいて、どのような質問をすべきかを教えてくれるでしょう。

これは、先ほどお話しした235インチのような結果が得られたときの問題と似ています。それに基づいて何を知りたいのでしょうか?何が関連しているかを判断できるアルゴリズムやヒューリスティックは存在するのでしょうか?少なくとも私にとって奇妙なことの一つは、Wolfram Alphaのツールでは、知識やデータなどに基づいて物事を予測できる範囲が限られていることです。しかし、私がこれまで取り組んできた多くの科学において、この科学の結論の一つは、世界で実際に予測できることには限界があるということです。結局のところ、計算的に還元できないプロセスが存在するということです。言い換えれば、システムが何を行っているかを見ると、それは一連のステップを経て、その動作を生み出しているのです。問題は、システムが何をしようとしているのかを、システム自身が行うよりも効率的に計算できるかどうかです。数学的な科学の偉大な成果の一つは、答えの公式を得ることにあることが多いのです。これは何を意味するのでしょうか?つまり、システムが実行するすべてのステップを追う必要がないということです。数式に数値を代入するだけで、システムが何をするかという答えがすぐに得られます。計算的還元不可能性は、驚くほど多くのシステムで起こります。システム側がそれを許さない、つまり還元不可能な状態です。システムが何をするかを理解するには、システム自体が実行するのと同じ一連の計算ステップを、事実上実行しなければなりません。答えにたどり着くための近道はありません。テクノロジーの構築においては、多くのテクノロジーが、計算的還元不可能にする必要がないように特別に設計されていると思います。機械には、3秒後には元の状態に戻ることが容易に予測できるような単純な動きがあります。つまり、私たちが持っているデータに基づいて世界で何が予測可能かという問題は、すべてこの計算的還元可能性と計算的還元不可能性という問題に行き着きます。予測できると期待できる特定の種類のものがあります。予測できないものも存在します。私たちはしばしば、予測可能なものとして技術を構築しようとします。しかし、自然は必ずしも同じようにはならないため、天気のように予測が非常に難しいものになってしまうのです。技術はますます予測困難になるだろうと私は考えています。なぜなら、技術がより効率的になるにつれて、計算上の還元不可能性に陥り、予測が困難になるのは避けられないからです。私たちにとっての課題は、こうしたあらゆるデータ、あらゆる知識を活用して、予測可能なものを予測し、何が起こるかを予測するために計算しなければならない事柄を可能な限り推し進めることです。

コースを走らせる速度が現実よりも大幅に速くなるように設定することはできますか?

Often. Often, but not always. I expect that lots of things that show up in biomedicine will have this computational irreducibility issue when we understand all these protein interactions and all sorts of details about how do we go from the genome to the actual biomedical, clinical kinds of phenomena. There'll be lots of computational irreducibility there, but chances are that we'll be able to compute things in big enough chunks that as a practical matter, by running enough computations, we'll be able to compute that if you apply this drug in this way then these things will happen, and so on. When it comes to a more extreme level, a case that I've thought lots about is the whole universe, and to what extent is computational irreducibility an issue in understanding the whole universe. One question is, how much data do you need to specify our universe? Is it the case that with an algorithm that's a few lines of computer code long, if you just run that for long enough, can you get a whole universe? How big does that underlying seed need to be in order to get our whole universe? And I think we don't know how big that underlying seed needs to be. Let's say we have the underlying data that completely specifies our universe, but then we have to actually go from that underlying data, that underlying algorithm, to the actual behavior of the universe. And one of the points is that this computational-irreducibility phenomenon implies that that's irreducibly difficult to do.

Would you have to run it for 13 billion years?

Well, I mean, OK, so in a first approximation, yes. The good news is that there are inevitably pockets of computational reducibility, and that's our best hope for being able to match up what we've already figured out in physics and so on with what the predictions of a particular model are. The universe, it's sort of obvious that there are pockets of reducibility, because there's lots of order that we can perceive in the universe. It's an inevitable feature. It's just one of these self-referential facts.

Computational irreducibility is like prime numbers in a sense, right? So as long as it has pockets of reducibility, it is not the fundamentally irreducible thing? It's not the universe that's computationally irreducible, it's . . .

It's the processes that go on. OK, so what is the universe? Is the universe the underlying code from which you can generate the universe? Or is it these dynamic processes that are going on inside the universe today? Or is it just one slice of those dynamic processes? This is the universe as it is today, whatever that means. What computational irreducibility talks about is how much information—if you want to predict what the universe is going to do, if you want to predict some aspect of what the universe is going to do, then you have to go from that underlying rule. You actually have to run it and see what the universe does. So, for instance, one of the types of things is, you might say, Is warp drive possible? And you might say, well, gosh, if you have the underlying theory of the universe, you should be able to answer whether warp drive is possible, but probably it isn't easy to answer. Probably that will be one of these questions for which it's effectively undecidable, because what you'll be reduced to from a mathematical point of view is to say, Does there exist some configuration of material which has this property and that property and that property given these underlying rules for how things can be set up? And that can be an arbitrarily difficult question to answer. And that's an example of what it means for there to be computational irreducibility. The thing with computational irreducibility is, what it tells you is that in order to find the outcome of some process, you have to follow through some number of steps. And that you can't always arbitrarily reduce the amount of computational effort that's needed.

近道はありません。

Right. One feature of that is if you ask a question like, Can such-and-such a thing ever happen even after arbitrarily long times?, that's a questions that, if there is computational irreducibility, you may not be able to answer in a finite way. If there was computational reducibility, then the fact that one's asking about arbitrarily long times shouldn't scare one, because even a thing that takes an arbitrarily long time one can reduce down to something that only takes some given, finite time. But if it's the case that there's computational irreducibility, then you can't expect to always do that reduction. If you're asking a question about what happens after arbitrarily long, it actually takes you arbitrarily long to answer that, and that's the origin of the phenomenon of undecidability that shows up in mathematics and Gödel's theorem and so on, and it's something which when applied to physics leads to this consequence that even if you know the underlying theory, you might not be able to work out what is technologically possible in that universe.

I think that most people would assume that if you know the underlying theory, you know all of the rules that govern the universe. And what you're saying is that that is not necessarily true, and to actually know what the rules are, you have to run the universe.

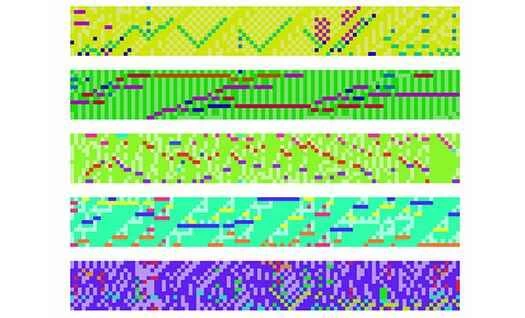

Evolution is actually closer to technology than one might thinkAnd that's the same fallacy, basically, as when people portray robots that act according to logic, they always portray them—in early science fiction, the fact that the robot had underlying rules meant that its behavior was in some way fundamentally simplistic. That's sort of the same fallacy, that if you know the underlying rules and the underlying rules are simple, then, gosh, you must be able to tell that, because there can't be an irreducible distance between the underlying rules and the actual overall behavior. In my efforts in basic science, one of the number-one observations was, if you look in a computational universe of possible programs, an awful lot have this property that even though the program is simple, the behavior is immensely complicated. When we do technology and when we create programs, most of the time we're trying to avoid the programs where the behavior is arbitrarily complicated. Those are the programs that work in some way that we can't possibly understand and it's full of bugs. We tend to aim in our current technology for things where the behavior is simple enough that we can readily see what its consequences will be. It turns out, I think, that one of the big things that will happen in technology—we can already see happening in the coming decades—is more and more technology will be found by searching the computational universe of possible programs, possible algorithms, possible structures, whatever, and we will be able to know that it performs some function for us, but if we look at how it does it, it will look very, very complicated and will not be something that we can readily predict. For example, when we build programs now in Mathematica and Wolfram Alpha, lots of those algorithms are found by algorithm discovery, where basically we're searching a billion different possible algorithms of a particular kind and finding the most efficient one that achieves some particular objective. When you look at that algorithm, you say, What is this doing? Sometimes we can understand it and we say, gosh, that's really quite clever of it. And sometimes you say, gosh, I can't be bothered to figure this out; this is way too complicated to figure out what it's actually doing, but yet we can see that it's doing the thing that is useful to us.

You can't figure out how it's doing it, but you know what it's doing.

You can see it's twiddling these bits in this way and, gosh, they always line up in this way at the end. And one can automatically prove that some particular property will always be the case, and one would never, as a human, trying to write the code, one would never have arrived at this kind of thing. It works in a way that is just utterly alien to a human who's used to creating code that does its thing iteratively, in a very organized way. When you look at it, it's like, wow, it's working, but it's working in this very complicated way. Now, we see examples of this quite often in nature, in biology, in physics, in other places—natural selection. Actually, evolution is a funny one, because evolution is actually closer to technology than one might think, because evolution has a hard time working on things that are really complicated. It's much better at, Well, let's just extend this bone a bit and see what happens, rather than—it's actually quite rare for evolution to go out and do something that is truly innovative. It's usually doing things incrementally in a way that's similar to a lot of engineering that we do.

Is it possible for nature, writ large—for the universe itself—to ever do anything that is anything other than incremental?

Yes! When you look at different things that happen in different physical systems, you can ask, Is it the same case in the way that fluid flow works in this situation versus that situation? They may not be connected. There's no requirement that the fluid flow be—from one situation to another, that it change its behavior only a little. If it was evolving under natural selection, it probably would be a requirement that it only change its behavior a little. Evolution doesn't tend to make these random steps that are absolutely dramatic. But the thing about a lot of nature is that there's no constraint that anybody should be able to understand what these things do. Sometimes we get confused because our efforts at doing science have caused us to concentrate on cases where we can understand what's going on, and that means we come to think, gosh, it's all set up to be understandable. But that's not true at all. It's just that we selected the cases that we studied to be those ones. And I think that what tends to happen in nature is that there's a certain amount of incomprehensible stuff that's going on where we can look at the underlying components, we can understand those, and then there's some computationally irreducible process that is what happens when those components actually run and do what they do. And in technology, a lot of what we do is we go out into the natural world and we find components that we can harness for technology. We find donkeys that we can ride on or something, or we find liquid crystals that we can use for displays, or we find other things out there in nature that we can harness for some useful human purpose. And one of the things that I know we certainly do a lot of is going out into this computational universe of possible algorithms, in a sense, the computational universe of all possible universes because that's—our universe operates according to some particular algorithm, but we can readily just go out at a theoretical level and just say, What are all the possible algorithms, what are all the possible universes that exist? And in fact, we can go and look at all those possible algorithms and say, Which ones are doing something that will be useful for some human purpose? And when we find one that's useful for some human purpose, we can implement it on our computer and maybe one day implement it in some molecule, and then it runs and does something that's useful for our human purposes. But one of the things that's important about that methodology—just going out and finding it in the computational universe—is that the thing we find is under no constraint to be comprehensible in its operation to us. When we do engineering, we do things incrementally, and usually it's the typical party-trick-type thing where you're shown two objects: one's an artifact; one's something that came from nature in some way. A very good heuristic is that the one that looks simpler is the one that humans made. Because most of the technology we build, it's very repeated motifs of circles and lines and things like this, and it's built to be comprehensible. I suspect that we're in the late years of when that will be possible. Increasingly when you look at technological objects, they'll be things that effectively were found in the computational universe, and they do something really useful. They're not things that were constructed incrementally in a way that's readily comprehensible to us, where their operation is readily comprehensible to us.

The current concept of how technologies are created is that they're built from the ground up. Basically what you're talking about is plucking something out of the computational universe that we can't understand and using it to power us forward.

Right. Remember, though, that the components of technology have often been incomprehensible. That is, people can use timber to make things even without understanding how trees manage to be strong. This is just a more extreme version. Typically, people have used materials with certain properties where the properties are fairly easy to explain. This is kind of a more extreme version of that, but now we're getting these things from this supply of algorithms rather than this supply of material objects.

We could keep going down this rabbit hole forever, I suppose, but let's pull it back a little bit. This search for the theory of the universe is not theoretical for you. This is something that you want to do or are doing right now. Are you doing it right now?

I've taken a break for the past couple of years because I've been working on Wolfram Alpha and all the things around it, which is actually very frustrating to me that I had to take this break, but—

I saw the TED talk where you proposed the notion of discovering what the actual initial algorithm of the universe is, and you said it would be within this decade.

それが私の希望です。

Seems remarkably optimistic somehow.

No, actually what I hope I said—who knows—is that I don't know whether our universe has a simple underlying rule. Nobody knows that yet. If it does, though, we should be able to find it. There's a lot of theoretical technology that you need in order to do the search, find out what you found, all those kinds of things. It's a lot of work. It's effectively a big piece of technology development to go and figure out—if you have a theory of this type, how do you see what its consequences are etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. We've done a lot of that work. The answer is: if the universe has a simple underlying rule, it's likely we'll be able to find it. My point of view is, if it has a very simple underlying rule, which we could find, it's sort of embarrassing not to have found it within a limited time. Now, it may turn out that the universe doesn't have a simple underlying rule. It might turn out that there's a rule for the universe but it's a million lines of code long, effectively. I think it's very unlikely.

How simple would you imagine it could be? How many lines of code would you guess, roughly what range?

Here's a way to think about that. If you start enumerating possible universes, you can—the best representation I've found for what I think is a reasonable way to get at this is using networks, transformation rules for networks, so you can represent that as code in Mathematica or something. And each of these transformation rules is probably two, three, four lines long, something like that. But what's perhaps a better measure is to ask, If you start enumerating possible rules for the universe, how many rules are you looking at before you find one that's plausible? If you look at the first 10 rules and start enumerating rules—there are probably different way to enumerate them; it doesn't matter that much which different scheme you use, because the way combinatorics works, the different schemes don't give you vastly different numbers—once you start enumerating, the first few you look at are completely, obviously not our universe: no notion of time, different parts of space are disconnected, all kinds of pathologies that are pretty obviously not our universe. The thing that I thought would be the case is that one would have to look through billions of different candidate universes before you find ones that aren't obviously not our universe. One of the things I discovered a few years ago is that that is not the case. Even within the first thousand conceivable candidate universes, there are already rules, already cases, candidate universes, whose behavior is complicated and you can't tell that it isn't our universe. Can't prove that it is our universe, but you can't tell that it isn't our universe So what typically happens is you'll start one of these things off and it will bubble around, and you'll follow it until it has—well, when I was last doing it, it was maybe around 10 billion underlying nodes—and then it's off and running and bubbling around, and you say, Is it our universe or is it not our universe? Well, this is where computational irreducibility bites you, because you ran it up to 10 billion nodes, but that's still 10-to-the-minus-58th second of the evolution of our universe, and it's really hard to tell at that point whether this thing that's bubbling around is going to end up having electrons and protons and god knows what else in it. That's where there's a whole depth of technology that effectively has to recapitulate—effectively what one's doing is some version of natural science, because you've got this universe that you're studying, it's in your computer, it's bubbling around, and then you have to kind of deduce what are the natural laws for that. What are the effective natural laws for that universe. You know what the underlying laws are because you put them in, but you have to say, well, what are the effective laws that come out and how do they compare to the effective laws we've discovered in physics? And so what I'm saying is that even in the first thousand candidate universes, there are already ones that might be our universe. And in fact, it could be that one of the ones that's sitting on my computer, that it is our universe, we just don't know it yet. That's the difficulty in making that connection between what we know now from physics and what we can see in this candidate universe. It's not where one's in a situation and saying, Oh my gosh, there's no way that rules this simple can produce the kind of richness that we need to be our universe. We're in a different situation where rules this simple can create incredibly rich and complicated behavior; we just can't tell exactly what that behavior is.

For me, it's sort of an interesting thing, because in modern science—post-Copernican science—one's led to think in this kind of humble Copernican way where there can't be anything special about us somehow. At some point, we thought we were the center of the universe, and that turned out not true at all. But now when it comes to our whole universe, we can imagine there is an infinite set of candidate universes. So the thing that seems wrong from a Copernican tradition is this: Why should our universe be one of the simple ones? You might say, Why isn't it just some random universe out there?

Is your theory that if one universe can be generated from simple algorithms, all universes can and have been? Or would be?

The only thing we can meaningfully talk about in science, as far as empirical science is concerned, is our actual universe: There's only one. Anything else we say about it is a purely theoretical thing. Now, the question would be—we might then say, gosh, what must be happening is that somewhere out there, not in any way that we can ever be aware of, but somewhere out there every possible universe must be going on. That might be a possible theory. It's not a testable theory. There's no way we could test that theory because we're stuck in our universe. And if that theory was correct, then the overwhelming likelihood is that the rules for our universe are very, very complicated, because if there are gazillions of universes out there and we're just in a random universe, the randomly chosen universe will be one with very complicated rules. It's like, each universe could be labeled by an integer. Well, there are an infinite number of integers. If we're a random integer, it's going to be a big integer. It's not going to be '8' or something. There's no reason for it to be 8 if it's just randomly chosen.

Now, I have a sneaking suspicion that when we really understand what's going on, that—typically, in the history of science, those kinds of metaphysical questions have crumbled because they weren't quite the right question, or things worked in a way that sort of worked around the question rather than having to centrally ask the question. My sneaking suspicion is that what we'll discover is that any one of a large collection of possible rules for the universe is equivalent in generating our universe. I don't know if I'm correct. That's just a guess. Something bizarre like that will happen, I suspect, to make that question of “Why this universe and not another?” not really be a meaningful question. It's a situation that's like—in a lot of cases in the history of science, people figure out a lot about how stuff works and then they say, “Well, why was it set up this way and not another?” And Newton was famous for saying, “Once the planets are originally set up, then [his] laws of motion can figure out what can happen. But how the planets were originally set up, well, that's not a question we can answer in science.” Now, 300 years later, we know a lot about how the planets were originally set up. One of the nicer things I always like about philosophers at that time, like Locke and people like that, would say: the fact that the number of planets is nine, eight, whatever it was in their day—that number is not a necessary truth about our universe. That number is somehow an arbitrary number. That was what they thought. They didn't think that number—just like I'm saying if our universe turns out to be universe number 1,005 or something, that that's just an arbitrary number. In their day, they couldn't imagine that you could compute the number would be seven or something. Now, in our day we know that if we have a star about the size of the sun and you have a solar system and it's about the age of our solar system, we know roughly how many planets there will be typically in such a thing. We can compute it. But in their day, that was an inconceivable idea, to be able to compute that. And I think that—I think we're at too early a stage. It feels a bit wrong to say, gosh, our universe must be one of the simple ones, so let's go out and search for it—because it seems like a sort of anti-Copernican kind of claim. It seems like a very arrogant claim about us and our universe. Why should we be one of the simple ones, not one of the ones that's incredibly complicated? My guess is, that question will resolve itself in some way that isn't quite centrally that question, but I don't yet know what that is.

The potential for your enterprise to have success and for you to actually discover, or determine, what the rule of the universe is relies on it being one of the simple ones.

That's correct. The approach that I know to take is one like algorithm discovery: search a trillion algorithms and see which ones are useful. And those are fairly simple algorithms that you are enumerating. There are fairly simple rules for the algorithms, so similarly—if our universe has rules that were a few lines of code long, then we could enumerate it and find it, but if our universe is the size of the source code of Mathematica or something, we'll never ever, ever find it by searching. It's just absurdly combinatorily far away.

I think it's a very basic fact about science—one piece of empirical hope, so to speak, in this direction is probably the most basic fact about science of all, which is that there is order in the universe. It might not be that way. It might be that every different part of the universe, every particle of the universe behaves in its own special way, but it's a fact noted by theologians a couple of thousand years ago that the most remarkable fact about the universe is that it has laws. There is order in the universe and it's describable by laws, and it might not have been that way. It might have been that the universe was full of miracles going on and all sorts of funky things happening that were not governed by laws, but in fact it has laws, and the very fact that it has laws and is orderly at some level shows that it is not as complicated as it might be. And that gives one some hope that it actually could be really simple. And simple enough that we, in the early part of the 21st century, can use our computers and go out there and find it. It's a little bit like the question: when does Wolfram Alpha become possible? I started thinking about Wolfram Alpha–type things 40 years ago now, and at that time it was probably impossible. If I had started building that when I was 12 years old, I would have finished it about the same time that I actually did finish it.

[笑い]

Maybe later. Some of the necessary intervening steps were done by you, and you wouldn't have been doing that if you were trying to . . .

I can't in any way prove that this is the right time in history to go see if there's a simple rule for the universe. The thing I find really surprising and remarkable and not what I expected at all is that one runs into “obviously not our universe” candidates as quickly as one does. I really thought that one would be searching billions, trillions of candidates before one found one to exclude very easily.

It's really a funny question: If there is one of these early universes that is a rich and complex universe that happens to not be our universe, that in itself will be a very bizarre discovery, because one could say, Well, there's a universe and it's got an eight-and-a-half-dimensional bizarre kind of particle in it, and it's got this and this. And it will be surprising. So one thing that's a question in physics now is, Is there a way to assemble the universe so that it's self-consistent but different from the way that it's actually assembled now? And we'll know that. In the worst case, by examining these candidate universes, we'll start to know answers to questions like that.

The fundamental aim of Wolfram Alpha: to foster and democratize computational knowledge At a purely personal level, the fact that it's possible to do Wolfram Alpha slows down at least my efforts at finding these things about the universe, because—for me, at least, I tend to be one of these people who works on large projects, and I tend to always have a supply of things that I think will be possible one day, and the question is, What decade can we actually try to do them in? Because if one picks it wrong, one will spend the whole decade trying to build infrastructure that even allows one to get to the starting point. This is the decade when computational knowledge has become possible, and there's a lot of just really, really interesting things that I think can happen from it. And I think the ways in which—people's expectation of how they interact with the world is really changing and I think can change as a result of computational knowledge, because people just don't expect that they can answer questions about the world now. The Web and search engines and such have changed that to some extent. There was a time when basic facts were not things that most people thought you could get easy access to. It took a lot of effort to get to basic facts. Now we can get to basic facts, but can we figure out specific answers to questions? Well, that's what computational knowledge is trying to do, and it will become routinely the case that people live their lives by being able to answer the questions that come up. Maybe they'll automatically be answered for them in some sort of preemptive way.

But I think one of the things, again, that has happened today is that there was a time long ago—early on our timeline, so to speak—when facts were only available to a few people in monasteries who had access to the books. And then facts got spread out—there were libraries, books people bought, education—and then along came the Web, and facts were pretty readily available for all. At this point, there's still expert question-answering but still very concentrated. If you want to know the answer to some question, you have to go find an expert, and that expert is in short supply perhaps, and it's all a big heavyweight process. I think what computational knowledge is going to do is essentially democratize that process and make it the case that if our civilization can answer the question, then you can answer it in five seconds. In other words, there may be questions that our civilization doesn't know the answer to; there may be questions where computational irreducibility intervenes and the question isn't really answerable. But if it's in principle answerable, then I think we can very much democratize that process and let anybody answer it quickly.

Is it fair to say that that is the fundamental aim of Wolfram Alpha: to foster and democratize computational knowledge?

That's what we're trying to do. That's the big effort. That's the thing: Absent these various realizations, one might have thought that with computational knowledge, we'll really not be able to get very far; it's very specialized and won't be able to be generally useful. And for me, that's the big metadiscovery of the past two years: that at this time in history, it's actually possible to do this. I don't think it will get progressively easier to do it—there's not going to be a dramatic moment when it gets much easier—but it sort of came over the horizon, it became possible, and it will gradually get easier. But this is the time.

To what extent does Wolfram Alpha's ongoing development still require it to be your primary focus?

Me personally? I'm spending all my time on this right now because it's really interesting and there's a lot of—the actual process of adding more domains of knowledge, we figured out the framework for how to do that. I get involved because I find it interesting and I think we can do it somewhat faster and better that way. But the main thing—given this idea of computational knowledge, you've only seen the beginning with Wolfram Alpha as it exists today. There's coming real soon, one of the big things is—today you communicate with Wolfram Alpha by feeding it pieces of text. In the near future, you'll be able to upload images to it. So, instead of giving it a linguistic description, you're giving it an image.

Will it tell you what the image is? Or what other things can you do with the image?

Not yet. It can't tell you what the image is yet. The typical thing is that you'll mix some linguistic thing with, I don't know, “closest paint color.” You got an image of some thing, and it knows the paints and it can see the image and figure that out. Or you might be able to say—there's all sorts of tricky things that you can do. Like there's a shadow in the image and we know what the geotagging of the image is and we know where the sun is and we can figure out based on the length of the shadow, we can figure out how high the thing is and all sorts of fancy things like that. The problem of recognizing images, we're working on that one, but it's a knotty problem. The most interesting things will probably be—one of the things that's always fun with this type of technology is that until you've built it to some level and you can really play with it fully, it's actually quite hard to tell what it will feel like. I know you can do a lot of really good toy things with uploading images and using images as input, but what will be the things that are the really, really useful things you can do? That will become clear once one is routinely doing it. Other things that are coming, like being able to get sensor data flowing into the system and asking questions of the data that's coming from some sensor that one has: you can say what types of flights are overhead and what speeds. You can get things from seismologists or weather stations. What I mean is your own personal data, like you connect it to your IMAP server and you'll be able to analyze the sequence of your receipt times of e-mails and things like that and be able to plot that as compared to when the sun rose on a particular day, and so on.

How else can we expect to see Wolfram Alpha develop in the near future?

I mentioned these things about preemptive delivery of information. Being able to provide knowledge based on what it can tell is going on for you, rather than based on what you specifically ask it, that's one type of thing. Another type of thing is watching what's happening in the world and being able to automatically figure out what's interesting. We have an unprecedented collection of feeds of all kinds coming into our servers, and we know all these kinds of things. We can see this peak in this curve: There's something. What we want it to do is figure out what's interesting. Of all the stuff that's coming in, what's newsworthy. What's worth telling people about and what's just the normal course of what happens on a Friday afternoon? That's another kind of thing: being able to figure out—because we do have the largest collection of data about different things going on around the world that anybody's every assembled. It comes in in real time, and we should be able to figure out what's happening, globally, what are the interesting things that are happening.

Another direction is, given that you have a complex task that you want to figure out how to do—that task might involve: you buy this component from this company, you connect it in this way, you do this, you do this. The question is, Can we figure out in some almost creative way, given that you describe your task in such-and-such a fashion, can we figure out how to achieve that task? How to perform that task? That's a thing we're trying to work towards. There's small cases. Like right now, if you type in some funny resistance, we'll be able to compute what pair of serial and parallel resistors will make that particular resistance. That's a very trivial case. But a much more complicated case is: One says, “This is what I want to make, and I'm going to describe it,” and I would go to a design engineer and say, “I want a thing that has this property and this property and this property.” They'll make it for me, figure out how to do that. That's a challenge that in a sense mixes together several different kinds of things. It mixes together—perhaps there may be a spark of creativity needed on the part of that design engineer. Maybe we can find that by searching some chunk of the computational universe. It mixes, but we have to know what actual resistors exist. How strong is this material? How far is it from this place to that place? So we have to have knowledge about the world. So the concept there is to what extent can we actually go from human description of the human's goals to how do you achieve those goals with the stuff that exists in the world and the stuff we can compute? And maybe a spark of inspiration that perhaps we can also get automatically. One of the most striking things to me is—in terms of this human inspiration thing—a few years ago we put up this site called WolframTones, which is a website that generates music based on a search of the computational universe. The thing that has been most bizarre to me about that is I keep on running into people saying, “I'm a composer and I use this site as inspiration.” That's sort of the exact opposite of what I would have expected. The role of the computer versus the role of the human. I would have expected the human as the one going, “I have an inspiration. I've got a human-created spark, and now I'm going to use the computer to work out that human-created spark and render it in the right way.” But instead what's happening is that these things that one is plucking from the computational universe, those are the sparks that the humans are then working through to develop into something that they find interesting. It's a simple case, but it's an encouraging sign. One of the big things that comes out of that is this mass-customization idea of, How expensive is creativity? What's the economics of creativity? Can you automate some of creativity? This idea of going from a description of a complex objective to how is that achieved—can you get the spark of inspiration automatically?